I once played a game of Hearthstone (for those unfamiliar, it’s an online card game) that ended with a moment of such unfortunate luck that I immediately quit the game and uninstalled it. I was pissed. I did everything right: victory was within my grasp and I had set everything up such that there was a 90% chance of winning outright, but a final moment of bad luck decided the outcome against me nonetheless. And I thought to myself: why am I playing this game that relies so much on factors outside my control when I could be playing something else less random?

In general, it’s because people like gambling. It is a well-known fact in psychology that inconsistent reinforcement does a much better job at keeping people (and animals) engaged in an activity. At least, this explains precisely why the developers of the game made sure to keep quite a bit of random chance involved the game outcomes. But I myself decided to instead play a game that felt more within my control: chess1.

Chess does not involve any luck; at least not in any sense that people commonly think of with the term. But one could imagine a game of PURE skill: i.e. one where a more skilled player ALWAYS wins against a less skilled opponent. This is not true with chess (or any other competitive game out there), as the best players will, on infrequent occasion, still lose. Imagined in this sense, luck is really just any source of variance from the expected result. And while chess is a game of complete information, there still exist many sources of variance in its games, mostly due to its sheer complexity! Let’s say you have two moves that look roughly equivalent. You cannot possibly compute every variation in the tree that results from each move, and perhaps to the distance that you can, they still look equal. And so, you choose one at a whim. BUT, as it turns out, if you were able to calculate one move further, the move you chose actually leads to an unavoidable loss! While the other move is able to avoid this fate and eke out a draw2. Alternatively, you may try out one equal opening over another, despite your opponent having very different comfort or experience between the two.

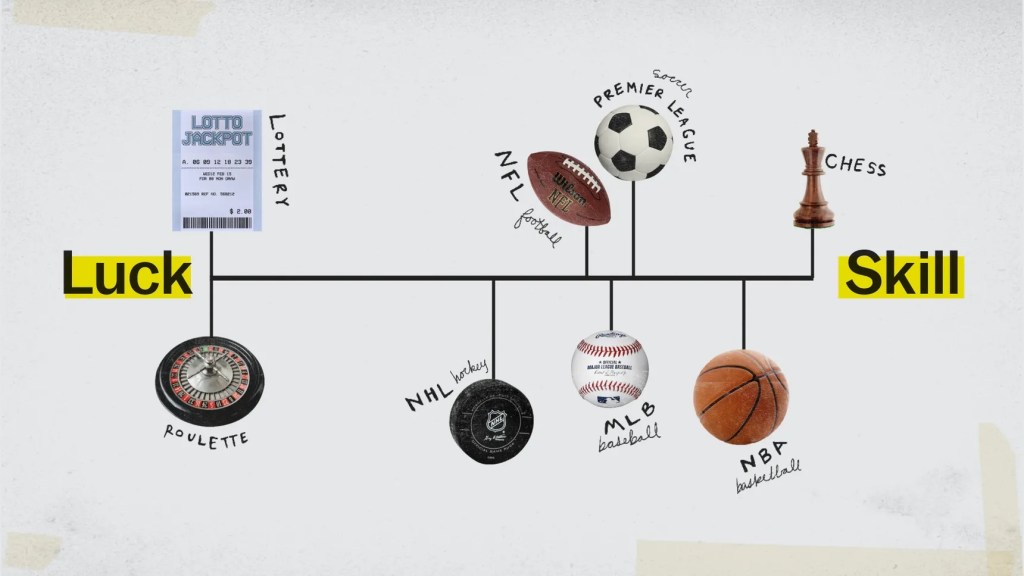

As it turns out, you can analyze any competitive game or sport, and use statistics to determine how predictable the result is (effectively, how much the previously observed skill of the competitors contributes to the outcome). Here is a ranking of the skill levels of some of the most major sports3:

Quite a few caveats exist, of course4.

Looking at various papers that analyze the amount of skill involved in different games, my favorite has to be “Measuring skill and chance in games” by Duersch et al5. In it they fit large databases of players and games to distributions of ELO ratings that best match their performance, and compare the standard deviation of the estimated ELO ratings as a proxy for the amount of skill involved in the game’s outcomes. The idea is that the more skill is involved in a game, the more widespread player ability/performance will be. Meanwhile games that are mostly reliant on luck will show relatively little rating deviation, as the better players will beat the worse ones with less consistency. They even use 50%-deterministic (where ELO ratings are estimated for a simulated dataset of players whose games are half of the time decided by a coin flip and half of the time decided deterministically) and 50%-chess (where half of the games in the chess database are replaced by random coin flips) as potential reference points for saying whether a game mostly comes down to skill or luck.

Poker appears to have about as much skill differentiation as 25%-chess (where 75% of the chess results are replaced by coin flips), indicating that its results are predominantly luck6.

(And so you and I have a good excuse the next time we lose in poker 😉)

But it is important to consider that the time spent on each game differs dramatically. The individual chess games are classical time control, meaning they would last ~2-4 hours on average. Meanwhile the poker outcomes are from Sit-and-Go tournaments, which would last around an hour on average. Thus a “skill-per-second” comparison would be slightly higher for poker relative to chess than the values obtained here. Mind you, I am certain poker would still come out very strongly in the “mostly luck” category.

I did notice something interesting after considering the skill-per-second idea. If you look at the ratings distributions7 of different time controls in chess, you notice the surprising fact that they are remarkably similar despite greatly varying time alotted. In other words, the amount of skill present in bullet chess is roughly the same as the amount of skill in classical chess, only the skills that are valued may shift somewhat (i.e., classical chess may reward opening preparation and concentrated calculation more, and bullet chess may reward time/mouse skills and positional intuition more). But if the amount of relative skill differences are the same in the two formats, then that means the skill-per-second is much higher in bullet chess than any other chess time control. If one were to play a set of many bullet chess games equal in total time to a single rapid or classical chess game, you would find much higher relative rating deviation (and thus even greater reliance on skill versus chance)8. Although classical chess shows lower skill reliance than tennis and go, I imagine that long sets of bullet chess would have them all beat.

So if you ever hear (the honestly initially-intuitive) argument that bullet chess involves way less skill than a long classical game, know that in truth it is actually the exact opposite. In fact, it may be the case that speeding up most games (e.g. having a really short time limit on poker decisions, or shortening a soccer field) would improve the amount of skill involved by increasing the number of competitive interactions between the players in any given time frame.

Of course, as mentioned before, inconsistent outcomes are more addicting. So why on earth would we do that?

- And so, as a humorous aside, I instead got quite addicted to chess for a while, from rather similar mechanisms to those found in gambling addictions. The addictive attributes of slot machines could be found in the bullet chess I was playing too: a steady, rapid, variable injection of reward. I would win roughly 50% of my games (since it always matches you with other players close to your skill level), and this potential dopamine hit would happen every couple of minutes.

Luck in Chess Rant

An example of this complexity-luck could be seen in game 40 of last years superfinal between the top 2 chess engines we have right now, Stockfish and Leela. After 71 moves of the game, both engines would agree that their position is very likely a draw (Stockfish estimating a 91.6% chance of a draw). But Leela chooses one bishop move rather than another, as both looked similar to it at a depth of 40 moves. Stockfish was suddenly unsure, however, with its more deeply calculated tree of 47 moves… and it’s best guess of its win probability jumps from 6.9% to 22.2%. They stumble through the best moves they can think of for the next 11 moves, and by move 83 stockfish finally thinks it is likely winning, and proceeds to win from there (Leela takes a longer time to realize it is in a lost position). With a little less time to calculate, and so a lower depth of evaluation, Stockfish may have made a similar mistake if playing as black.

Yet another form of “luck” in chess can be demonstrated more directly with human players. At the European Teams Chess Championship last year, we could see this in the game between Nikolas Theodorou (a strong 23-year-old grandmaster, ELO rating 2619 at the time) and Teimour Radjabov, a super grandmaster rated 2745 and ranked #14 in the world for classical chess at the time. The game was a wild ride of sacrifices and a crazy mating attack; but what was most notable may not have even been what happened on the board, but on the clock. Nikolas upset Teimour in a mere 19 moves, having started with an hour and 30 minutes on the clock and ended with an hour 28 minutes and 54 seconds (with a 30 second increment on each move). The kicker is that Nikolas played with 100.0% accuracy, despite how thorny and complex the position was.

Was this due to godlike inspiration at the chess board? No, it was not. It was due to a fastidious preparation with a computer beforehand, and Teimour had sumbled precisely into one of the move orders (“lines”) that Nikolas had analyzed beforehand. In fact, a great deal of effort in classical chess goes toward “opening prep”, where players analyze many complex lines and positions that can arrive out of an opening, hoping to prepare a trap for an opponent that can lead them down a path where the preparing player already knows the best moves beforehand. Given their respective ELO ratings (and who started with white), one would expect Teimour to win 43% of their games, draw 43.1% and lose 13.9%. But he inadvertently stumbled into one of Nikolas’ prepared lines, and so the game was virtually decided.

It is very rare that a chess game can follow a prepared line to the end, given how many countless variations exist. Usually opening preparation is just designed to lead into a position where the preparing player has a small advantage, or at least where the position has been better understood prior. While certainly the level of opening preparation (and ability to avoid that of others) contributes to a player’s ELO rating, this game is a prime example of where it can function as a source of variance contributing to an unexpected outcome (i.e., the better player losing). In this sense, it also factors in as a source of luck.- The Success Equation by Michael Mauboussin, using methods derived by Tom Tango. This Youtube video by Vox does a pretty good job of summarizing it

- I think the analysis is cool, but should perhaps be explained better. In particular, I think it’s important to note that it is not a description of how much skill contributes to the outcome in that type of game generally, but rather how much the ‘relative’ differences in skill ‘within a league’ contribute to the outcomes in that league compared to random variance (i.e. luck). In other words, if you imagined a league where every team was equally skilled, this analysis would correctly show that the outcomes of their games were 100% determined by luck (as they are all equally skilled!). As such, balancing mechanisms such as salary caps and restrictions on free agency would lead to more balanced leagues and thus a LOWER contribution of relative skill differences between the teams towards the game outcomes. So the NFL having a lower rank compared to basketball may be due to a greater influence of luck in season rankings, or be due to the teams having better skill balance overall due to league rules (Miami Heat Big Three, an example of poor league balance imo). They also do emphasize that the length of the seasons contribute greatly, as the 16 games in the NFL will be more prone to the vagaries of random chance than having 162 total season games in the MLB.

- Measuring skill and chance in games by Duersch, Peter, et al.

Luck in Poker Mini-Rant

There are a wide variety of analyses on skill contributions in poker, e.g. How much does success in online poker persist across years

Around 1000 hands (~13.33 hours if only at one online table) of online poker are needed for skill to be more relevant than chance in your net loss/earnings

How well do pros do compared to average players

Trying to work out equity gains/losses from individual decisions in an actual game

A cute theoretical analysis based on a theoretically optimal player compared to average and beginner players

I’d say the gist is that yes, with enough games and money you can demonstrate your skill advantage in poker (as good pros do over long periods of time), but the amount of games and money required (a lot) put poker firmly in the mostly-luck category of games by almost any metric.

If you want to make money via poker, rather than aiming to be a pro player competing at tournaments I’d recommend waking up and hitting up Vegas casino tables at 4am and trying to find the least sober people around to play with (if you aren’t bothered by any potential moral qualms, that is).- Lichess Rating Distributions

- Repeating observations increases the chance you have a good representation of the underlying truth. For example, if you have a 2/3 chance of winning a single game against someone, you’ll have a ~74% chance of winning two out of three games against them:

(winning first two games, no game three) + (winning first and final games) + (winning second and final games) = (2/3 * 2/3) + (2/3 * 1/3 * 2/3) + (1/3 * 2/3 * 2/3) = 0.74074074.

Leave a comment