(albeit abbreviated)

There are many ways we all consistently misjudge. Here is a small list of the big ones, plus the ones that I find most interesting or most helpful to be aware of, organized into rough categories: 1

Group 1: I’m Special!

Egocentric Bias – We overestimate ourselves, and may incorrectly weigh our own perspectives. For example, we see ourselves as less biased, more capable, and more resilient than most others. We also assume people agree with our opinions. However, there also exist worse-than-average effects and imposter syndromes in certain settings.

Barnum Effect – We believe that vague descriptions “tailored towards us” really do match us specifically. In other words we believe fortune tellers are making predictions specific to us when really most people would agree with their statements. Also astrology and personality tests. That said, I’m a Scorpio, and take issue with how Co-Star describes me (our best careers are just villain descriptions???).

Fundamental Attribution Error or Actor-Observer Bias – For others we assume their actions are mostly the product of their personality, whereas for ourselves we often emphasize the role our situation plays.

Third-Person Effect – We believe that mass media messages have a greater effect on others than on ourselves. We probably imagine ourselves more resistant to all types of sociological phenomena.

Overconfidence Effect – Answers that people rate as “100% certain” turn out to be wrong 20% of the time2. This discrepancy is most dramatic when we believe we are at our most confident.

Planning Fallacy – Perhaps an extension of our overconfidence or optimism bias, but we underestimate the time it will take for us to complete tasks (and also underestimate the risks and overstate the expected benefits). In contrast, we also tend to overestimate the time it takes for others to complete tasks.

Spotlight Effect – We believe that others notice us much more than they really do.

Group 2: Interpersonal

Ben Franklin Effect – Getting someone else to perform a small favor for you can be even more effective than performing a small favor for them when making friends. Ben Franklin was able to do this by getting a rival legislator to lend him a book, and after expressing great appreciation for the favor they then became great friends.

Cheerleader Effect – We perceive people as more attractive in a group than in isolation.

Halo Effect – Positive and negative traits spill over from one personality area to another. For example we believe physically attractive people are more intelligent, competent, and moral.

Reactive Devaluation – A proposal is devalued if it appears to originate from someone we dislike.

Bandwagon Effect and Groupthink – We tend to do and believe the same things that many others do and believe, thanks to social pressure. Most impressively demonstrated in the Asch Conformity experiments3 where participants would frequently (35.7%) say the obviously wrong answer just to conform to a group of actors purposefully saying the wrong answer out loud. Helps explain why people on each side of the political spectrum just happen to adopt the same viewpoints on most issues, even though things like gun control, taxes, and abortion are almost entirely unrelated.

Authority Bias – We attribute accuracy to authority figures unrelated to their argument’s content, and are more influenced by their opinions. As demonstrated in Milgram’s famous experiments4, we can be pressured to take deeply discomforting actions such as painfully shocking strangers when commanded to by authoritative figures.

Just-World Hypothesis – People want to believe the world is fundamentally just, and so bad circumstance is rationalized as being deserved by the victim. How much of this is due to religion and how much is innate, I wonder?

Group 3: Decision-Making

Hungry Judge Effect – Present sensory feelings can impact unrelated judgments. Named for a study that found parole boards to be much more lenient when well-fed5… it is a disputed result though.

Conservatism Bias – We are usually too set in our beliefs, and ought to change them more in response to new information.

Confirmation Bias – We pay more attention to information that confirms the notions we hold already, and disregard contradictory results.

False Priors – We have many, many wrong assumptions regarding ethnicity, gender, etc. Combos well with the above two, eh?

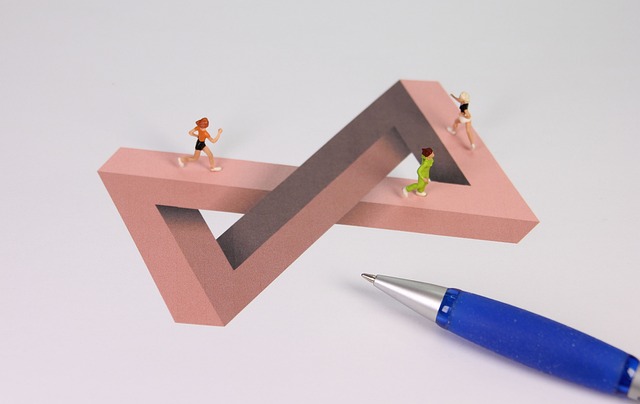

Apophenia – We always try to find patterns, even when none exist. This can cause us to believe in illusory correlations or in, say, winning streaks while gambling.

Gambler’s Fallacy – We think that future events are affected by past results, even when they are independent. For example, a gambler who has seen the roulette wheel land on black 5 times in a row may believe that a red is much more likely now.

Base-Rate Fallacy – We forget the general prevalence of things in favor of more specific nuances. If you are told a person is exceedingly interested in dinosaurs, you might assume they are more (or similarly) likely to be a paleontologist compared to an investment banker, but in fact investment bankers are just so much more common than paleontologists that it should overwhelm that one piece of information.

Selection and Survivorship Bias – We can forget to account for what filters may exist prior to information reaching us. A good example of this is reading about the success stories of millionaires and celebrities, while not recognizing the large majority of people that failed when trying out similar life and career strategies. High-risk, high-reward is not necessarily a life strategy worth emulating.

Contrast Effect – Compared to a recently observed item, the differences of a new stimulus are enhanced. So if you show a super overpriced object to a consumer first then they may take an only somewhat-overpriced item as much more reasonable afterwards!

Distinction Bias – We view two objects as more different when viewed at the same time compared to when they are viewed separately. (Is this why I take forever to decide between grocery items that are basically the same?)

Proportionality Bias – We assume that big events have big causes, potentially contributing to our acceptance of conspiracy theories.

Truthiness – People believe statements are true

a greater proportion of time

if they are easy to process,

repeated more, or if they rhyme!

Group 4: Weird Preferences

Effort Justification and the Sunk-Cost Fallacy – We often try to justify our efforts, even when said efforts aren’t justified. In fact, we often double down, even if it was the wrong decision. So if you’re watching a movie that sucks, don’t finish it just for the sake of getting your money’s worth.

Loss Aversion – Losses imbue us with greater emotional weight than equivalent gains, leading to irrational risk aversion.

Disposition Effect – We sell the assets that have gained in value and hold onto the ones that have lost value. Similarly, we would prefer a scenario of gaining $50 to one of gaining $100 then losing $50, even though the net result is the same.

Status Quo Bias – Exactly what it sounds like. We like things consistent, often even when slightly better alternatives exist.

Hyperbolic Discounting – We very strongly value quick reward over longer-term value. Valuations fall rapidly for earlier delay periods (e.g. from now to one week) then more slowly afterwards. In one study people were indifferent between receiving $15 immediately or $30 after 3 months, $60 after 1 year, or $100 after 3 years. Compared to this growth curve, basically all investments are not worthwhile.

Impact Bias – We tend to overestimate the intensity and duration of our feelings given any future outcome. E.g. we might imagine receiving a job offer vs getting rejected as greatly affecting our long-term happiness, when in truth it has little impact.

Scope Neglect – We are roughly willing to pay the same to save 2,000 birds as 200,0006. And our actions favor saving higher proportions of small groups rather than a larger total number of people (e.g. preferring a project that saves 102 out of a group of 115 affected people to one that saves 105 out of 247 affected people)7.

Compassion Fade – One identifiable death is a tragedy, but a million really is a statistic.

Group 5: Memory

End-of-History Illusion – A belief throughout our lives that we will change less in the future than we have in the past.

Declinism – We tend to view the past more favorably (rosy retrospection), and the future more negatively.

Hindsight Bias – We tend to imagine past events as being easily predictable or expected, even when they weren’t.

Availability Heuristic – Effectively a recency bias. Ideas that are more easily recalled (say because of greater or more recent exposure) are believed to be more important and impactful. This leads us to believe wild stories on the news are much more common than they truly are, and overvalue recent experiences when making future judgments. For example, investors in 2009, 2020, and 2011 routinely overestimated investment risk after a terrible year in 20088.

Peak-End Rule – We largely judge experiences based on how they felt at their peak intensity and how they ended, rather than the total sum or average of each moment in the experience. Duration, too, means little to us after the fact.

Well-traveled Road Effect – We incorrectly underestimate the duration taken on familiar roads, and overestimate the time taken on unfamiliar ones. In other words our experience (or remembrance) of time is highly subjective9.

- For a more exhaustive list, check out Wikipedia’s List of Cognitive Biases!

- Confidence in the Recognition and Reproduction of Words Difficult to Spell

- Asch Conformity Experiments

- Milgram Experiment

- Extraneous factors in judicial decisions

- Measuring Nonuse Damages

- Scope Insensitivity

- Availability Bias

- Subjective Lifespan

Leave a comment